Wednesday, January 16, 2008

STARS Upgrade on 1/19

Tuesday, January 08, 2008

Searching for the Obvious?

Let's say your professor has been brave - or foolish - enough to approve your term paper topic "The Cultural Significance of Moby Dick." He probably thinks it's a great topic, in fact. Everyone knows about Moby Dick, right? Moby Dick is.....well, it's obvious. It'll be easy to research. There's probably no limit to the ways you can explore the topic - there's the whale, the book, the name itself, the sea, the search, the author, the reading public, the interpretations, the editions, the genre, the spin-offs, the movies, the Classics Illustrated comic book ..... you get the idea. Did Moby Dick look like something? Google Images indexes aver 157,000 pictures of the creature or of cultural items attached to its name. You could probably find hundreds of Grade A term papers for sale on the subject, if you looked. This could be the easiest assignment you ever had.

Not only your instinct but your instruction will be to base your paper on articles and texts that have been written by scholars, experts, and published in time-honored, peer-reviewed fashion. That much is obvious. If you're in college, your research should be based on textual material mostly written by college professors, and found in journals edited by professionals who know as much about the subject as the scholar they're publishing. Right away you will think of Academic Search Premier, or the MLA Bibliography, or the

In the MLA, "Moby Dick" brings up 1123 hits. Moby Dick and "significance" gives us 2, but Moby Dick and "cultural" gives us 12. Hmmmm. What about Moby Dick and "cultural significance?" Nothing, but then, why should it? Maybe professors don't really think that way. Isn't everything having to do with culture "significant" anyway? The words describing the topic you chose were really only a way of exploring and narrowing areas of relevance, a tentative focus. It might make sense to ignore the terms entirely! Why not search Moby Dick and "influence?" That brings up 35 results. Isn't ”influence" pretty much the same as "cultural significance?" But in JSTOR “Moby Dick and cultural significance" brings up 858 results. Why is that? One clue might be that MLA specializes in literature, and JSTOR searches across many disciplines - history, psychology, political science, sociology, art, Jewish Studies. Did Moby Dick signify more in the world of the social sciences than in the world of literature? Who's to say? Does JSTOR have better indexing? Who knows what's "better?" Maybe you should have chosen a better term than "cultural significance." After all, no one can doubt that this famous iconic 1851 novel created waves that crossed 16 decades, even though its author died in obscurity?

In Lexis-Nexis Academic Universe, "Moby Dick and cultural significance" brings up 6 results when searching "all available dates". But JSTOR searches a much wider range of dates, and MLA searches journals Lexis-Nexis doesn't include. Hmmm. Maybe searching critical, scholarly, peer-reviewed text is the problem. Can Moby Dick have signified in ways and places foreign to literary search terms? Every search engine depends on language to locate text. But search engines depend not simply on language but on a language - a particular way of representing meaning and context.

The same word may mean different things from one database to another or from one discipline to another. Different journals are included in different databases, date coverage varies, keyword indexing and clustering styles vary. Differences in subject descriptors, algorithms, the frequency of updating, graphic user interfaces, languages searched, and search options vary. So it may make sense to abandon the search terms "cultural" and "significance," which are primarily literary, and assign relevance just because we tell them to, and get down to more gritty ways of exploring the topic: searching all over the place for "Moby Dick." Our assumption will be that whenever, however and wherever it's mentioned, it will encapsulate in some way its associations with a world that keeps giving it new meaning.

Maybe "Moby Dick" means something entirely different to a music database than it does to literary or sociological database. From Grove Music Online we learn that a musical work of Armando Gentilucci's from 1988 was entitled "Frammenti sinfonici da Moby Dick." Who was Armando Gentilucci and why did he think Moby Dick could refer to something musical - so much so that he also wrote an opera entitled Moby Dick? And whose words did the opera's libretto use? Gentilucci wasn't the first to set Moby Dick to music. Douglas Moore, we learn, born in Cutchogue, NY, wrote a symphonic poem entitled Moby Dick in 1928. And Tobias Picker, we know, wrote a beautiful tone poem in 1983, The Encantadas, based on Melville's own text for "The Encantadas or The Enchanted Isles, " a narrative about his travels in the Galapagos Islands. Would he have chosen that text if Melville's fame hadn't been established earlier by the canonization of Moby Dick? Isn't that what "cultural significance" is about, even if nobody has ever described Picker's work with those terms? If it were me, I'd take a chance and let my professor play with the idea, though it didn't exactly emerge full-blown from a "scholarly article". If your professor isn't impressed with that, you might mention (or show) her some of Rockwell Kent's wonderful woodcuts - works of art that stand on their own - that illustrated the R.R. Donnelly & Sons 1930 edition of Moby Dick. A simple search of ArtStor will easily lead you to it.

But forget literature, music and art. What if you searched psychology? Doesn't everything "culturally significant" have psychological roots as well? A quick search of "Moby Dick" in PsychInfo brings up 34 results, including Moby-Dick and Compassion, by Philip Armstrong; Society & Animals, Vol 12(1), 2004. pp. 19-37 and The Narcissus legend, the white whale, and Ahab's narcissistic rage: A self-psychological perspective by Efrain A. Gomez; Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis & Dynamic Psychiatry, Vol 18(4), Win 1990. pp. 644-653. If psychology is fruitful, maybe philosophy will be too. The Philosopher's Index produces nine results right away, including John Bernstein's Herman Melville's Concept of Ultimate Reality and Meaning in "Moby-Dick", Ultimate-Reality-and-Meaning, 1982; 5: 104-117. It doesn't get much more significant than that. Well, then. What if we forget "scholarship" and look at our "culture" directly, say in today's news? Lexis-Nexis Academic Search Premier gives us 259 hits from major worldwide newspapers just in the last three months, like, "Rove may have doomed GOP by overreaching," by Richard Sisk, New York Daily News, an article that quotes the great Karl saying "I'm Moby Dick!" - alluding no doubt to his uncatchable quality.

Why not try Contemporary Women's Issues? You may not find much more than a passing reference to the whale, but some women still invoke him when they feel their self-image threatened: "Those of us who looked like Moby Dick in our eighth month will be surprised that women become 'girly' then.” said Meredith Douglas in The Nation in 2001 review of a book on motherhood. But do pregnant women really look like whales? How about trying a Lexis-Nexis search of Federal Environmental Case Law? In 2002, deciding a complex case involving whale-fishing and the State of Washington's Makah Tribe, a circuit judge opened his amended opinion with this quote: "While in life the great whale's body may have been a real terror to his foes, in his death his ghost [became] a powerless panic to [the] world." Herman Melville, Moby Dick 262 (W.W. Norton & Co. 1967) (1851). This modern day struggle over whale hunting began when the

Why expect anything from the Ethnic Newswatch database, which indexes thousands of newspapers from ethnic and racial groups around the world? Why indeed? A quick search found this entry: 'Moby-Dick' b'Ivrit! 'Moby-Dick' read in Hebrew for first time as part of marathon,Trachtenberg, Rona. Jewish Advocate.

And what if we search the Library of Congress' American Memory website, which comprises hundreds of digitized scholarly exhibits about American history and culture? Sure enough, we are quickly pointed to a scanned copy of a review for the novel that appeared in the United States Democratic Review, Jan., 1852. The unsigned review concludes:

”But if there are any of our readers who wish to find examples of bad rhetoric, involved syntax, stilted sentiment and incoherent English, we will take the liberty of recommending to them this precious volume of Mr. Melvilles."

Uh-oh. I guess that writer thought he was being culturally significant.

Friday, April 27, 2007

DOES GOD EXIST ONLINE?

DOES GOD EXIST ONLINE?

Theme and Variations

by Paul B. Wiener

Librarians know better than most people how easy it is to find the answer to a question. They also know how hard the search can be. That's because most questioners are - or believe they are - looking for the right answer to a question. Since I've been searching for God since at least the age of 6, I decided to use my skills to demonstrate a problem common among information professionals in a way nearly everyone could relate to. When is information the right answer? One answer to this quickly became apparent: when you ask the right person the right question. But who is that? For this study, think of "the right person" as a search engine or a search box connected to a database and to the World Wide Web. All information-gathering search engines, after all, are built by people. They scan, filter and retrieve whatever it is that other people from every walk of life all over the world have thought and documented and indexed in some way. In some way: aye, there’s the rub. Seekers may swim alone but they use different strokes in a sea of people to keep them afloat.

A poll showed that 82% of Americans believe in God (or did in

Does God Exist? Some would argue that that question lies behind every other question we ask, every answer that we seek - whether the answer appears as numbers, words, pictures, colors, or sounds; whether the questions are phrased in political, religious, scientific, logical, Boolean or historical terms; whether the authority sought is peer-reviewed, hearsay, traditional, oracular, podcast, rumored, tabloid, tyrannical, literary or research-centered. Surely if a humanly-constructed database or search engine that depended primarily on verbal search terms was worth its mettle - its reputation and cost, its publicity - it could provide guidance on this most elemental search, as well as insight into the quirks and surprising behaviors of search engines themselves, few of which openly declare their origins. And of course, as every librarian knows, there was the possibility of finding a definitive answer to the question. It might resolve the oldest question ever asked! Mind you, I wasn't looking for a one word answer, though I wouldn't have rejected one either. For what it’s worth, download the complete chart to see what happened.

It was hard to know when to stop. But after I'd had my fun, I had to confront the inevitable: had I learned anything from this little study? Was it fair even to have expected anything new to surface? About God? About the search for God? About search engines? About the searcher? The only way I could draw conclusions, I realized, was by immediately ignoring the obvious: that all "conclusions" would be conditional, if not simply false - tainted and problematic. To say there were too many unavoidable, often unknowable, variables inherent in my search strategy is perfectly obvious: generalizing from the results might insult the human condition prompting the agony behind the search. And yet, how human it is to generalize and conclude from evidence. How human it is for librarians to depend on computing algorithms! It was as impossible to ignore the lesson as it was to ignore the variables. My experiment provided librarians who need to believe that information is sacred with evidence that, in a way, it is if you say it is. Information is also as sacred as ignorance. Try searching for ignorance. Let me try to present it as unequivocally as possible.

First, hail to the variables! A question like Does God Exist isn’t really asking for information, it’s asking for trouble. But what choice do we have? Questions like What Is Art? Is self-medication bad for you? How can we clean up the environment? Is outsourcing good? Is entrapment a legitimate way to combat sexual predation? Has the UN ceased being necessary? Is the Mona Lisa more beautiful than

Many search engines never explain to their users how they work anyway, and few users read carefully - if ever - the Help, FAQ or About links that might tell them. Many librarians also are as ignorant of the engines they use to drive curiosity as anyone who gets in a cab on a rainy, crowded street and expects to get to a destination safely. They know the engine is there, and that it works. Moreover, as we have seen, results are often displayed in uniquely graphic and textual ways, depending on the engine, its designers, the indexing parameters available, the code language, and the foresight and empathy the programmers and publishers have for the sensitivities of the ignorant. And the scope of the database is an important variable; it is almost always changing: what journals, reports, newspapers, studies, languages, libraries, private archives, songs, personal pages, translations, records, accounts, content/site filters, keystroke entry options are left out, and are we even aware of them?

Those are just the easy variables. What about the day or month the search was done – was it 14 weeks ago or yesterday? The databases I chose to use? Because I hadn’t heard of the other ones? For this project there were at least 400 others that would have been worth searching. Are these databases ones you had to use, because of the institution or ISP you depend on? What language were you searching in – was that because it’s the only one you speak? Every language, after all, will associate search terms with linguistic concepts that, culturally speaking, may mean something only in that language. And what about the search query itself? Why "god?" Is that the only word we have for invoking a sense of what's greater than our selves. And if god doesn’t exist, why all the fuss? Mon Dieu! Words can only do so much. "God" can be another name for the quantum physics, for intelligent design, for Shakespeare or Diogenes, for an orchid, a puppy, the concept of zero or of love, for excellence, for a perfectly-done Form 1040, a balanced budget, the shape of a snowflake, a game of baseball or Go, for the internet....Whatever we ask of a search engine, it can only work with the terms we humans give it. And only we can ascribe power to what it finds. The search engine doesn’t know, but we users always know what we meant. The information we're seeking is already out there; but it only resembles the answer we think we’re looking for.

Is an answer or a fact the same when spoken in the language of science as it is when spoken in the language of literature or history? It’s impossible to tell from our results, but ask yourself this: does wisdom grow in literature the same way it grows in science? Of course not. Wisdom doesn't accumulate in literature at all. Can we compare the answers to the “meaning of life” in Hamlet, Nausea and Being and Nothingness? In my little game, when I entered Does God Exist, even though I said a search engine is created by people, I wasn’t really asking a who, I was asking a what – and a what doesn’t think. A search engine is a process that symbolizes and particularizes human ignorance. All the information I found about god was already there -processed, coded, written, known, past - maybe even true. But if the truth of god were known, what would be the point of praying? Is finding god as easy as choosing information? Choosing answers is what librarians enable their patrons to do. As wide-ranging as they can be, a search engine is also a vehicle for suppressing the alternatives to every answer. But it’s possible God speaks no language that recognizes questions.

The apparent futility of my search - neither its failure nor its success proves anything - mirrors the problem many people experience who seek information online: do I know if I'm asking the right question, looking in the right place, asking the right person, asking at the right time, understanding the answer, using the right language? Can I tell the difference between information and results? Is what I'm finding even information? Is it enough? Online, almost everything that can be described can be found; everything competes for truth, and all the authorities compete for pole position. Information may be easy to find, but search engines don’t deal in truth. If I found God, would I know it? God's existence belongs to a long list of truisms that can never be turned into phenomena, like pornography is unhealthy, technology is evidence of progress, history repeats itself, all men are created equal, rape is not about sex, father knows best, there is a smallest particle of matter, knowledge is power? These intuitions and observations are never based on repeatable evidence, but the results of a search engine query often are – and often aren’t. God does exist online: the proof is in the algorithms. That will have to do for now.

30 March 2007

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Is Information Literacy Possible? Part I

|  |

Many believe that those who can't use the invisible web - that small group of specialized, membership- and fee-based databases and web sites - are at a great disadvantage in terms of the learning and scholarship they can achieve. These unfortunates are said to be "deprived" of a great resource. They're taught to believe that the "visible" web - the free World Wide Web we all know - limits investigation and represents only the tip of the iceberg of wisdom. Nearly the opposite is true. The carefully controlled databases and research protocols that dominate the invisible web and reach out to students, scholars and professionals do offer scientific solutions to specialized ignorance, and the information they offer is frequently presented as neatly packaged answers. But they have little truck with the arcane knowledge, the proud displays, experiments, claims, creations and discoveries of the obsessed and the fanatic, the auto-didact, the prophets, wizards, self-absorbed oddballs, and subterranean hobbyists possessed by their one- or three-track minds - the peerless folks who comprise most of the conscious seekers on the planet.

In academic libraries, nearly all librarians like to teach students and professors how to use the databases their library subscribes to. My library spends nearly a million dollars a year for the privilege of accessing them. Nearly all these databases have been created by academies - educational, governmental, professional, publishing, or some combination of these. The institutional sponsors of a database vouch for the peers who provide the "peer-reviewed" encomium that makes information on these databases acceptable to most serious students and researchers. Editors and information technologists gather, digitize, index and publish millions of articles and reports from thousands of journals by experts in a given field - chemistry, psychology, music. Sometimes they make up new fields, like cultural studies, or bionanotechnology. They know the terminology, the research protocols, the controversies, the latest developments and the names of the best and the brightest. But as good as they are these experts are still lucky, privileged, professional, proudly published universalists in a world of nominalists. In a world that's often looking for a particular something it can't quite describe - or maybe something else - universalists are frequently of little help. They find and name what we all suspect is there. But how do we know that's all? Discovery, exploration, accident, and mistakes uncover the unexpected, and are also leading generators of information. And nearly all databases created by committees point toward familiar, cited, hierarchic and respectably formatted information.

|  |

I maintain that bibliographic instruction bears almost no relation to information literacy. They are separate planets. You don't teach "information literacy" any more than you teach "linguistic literacy." Sure, it's possible; but what you teach is literacy in a particular language. Similarly, you can teach literacy in a particular type of information. Are there types of information other than false and correct? I think there is. Everything about the way something is expressed, perceived or made known is informational. You look for information, you recognize it, in its presentation, as much as by its content. Why else do you think everyone makes fun of PowerPoint? Because it can make anything look like information. If it's the concept of "information" you're teaching, you must make it clear that it speaks in many "languages." Both B.I. and information literacy are favorite terms of academic librarians everywhere. Both terms were invented to reinforce the myth that science actually deserves to be in library science. Though few librarians have ever bought into the concept, teaching pseudo-scientific approaches to information-seeking is now seen as a professional responsibility of librarians, with effective, proven pedagogies and outcomes. In a sense, it is the geek version of the old Reader's Advisory.

Much of B.I. instruction may be short-changing high school and college sudents everywhere, as well as selling the practise of librarianship short. For if anyone knows that information can be found in places far removed from peer-reviewed articles, reports, statistics and studies, most of which are closely bound to databases created by profit-seeking businessmen who charge people dearly to use it, it's librarians. Librarians know that information has a thousand shifting shapes, and is represented by irrational, sometimes invisible, unindexable, often nonverbal processes and patterns as much as by searchable ones. Real information is found everywhere and bears only a passing relation to truth. Indeed, it's much more interesting than truth. Teachers who accept and explore only peer-reviewed information are in effect telling their charges to look for a version of a recognizable truth that has passed muster - canonical truth, perhaps, but not the whole truth. But an education isn't worth very much if you learn nothing but the truth. Sure, there may be lots truth in the databases librarians promote. There's a lot to go around, and academics will fiercely cling to their share. But to live, truth needs room. It doesn't speak from a source code alone; it also speaks through a medium.

There is nothing wrong with using peer-reviewed sources of information. They are usually solid, authoritative, responsibly formatted, and morally unobjectionable. You can check their provenance, and find their proper bona fides in the "about us" links. Databases offered by First Search, Lexis-Nexis, Wilson, and Gale are often accompanied by complicated, ingenious search engines loaded with features and options that take time to learn and use. They can demand such a detailed inquiry that an undergraduate may become disgusted by his ignorance. He often flees to the free web, where his teacher says he shouldn't expect authoritative information. But does he know what to do there, besides Google? In a way, the professor is right. Authority is what most databases specialize in providing. They are often the only place to find reviews, criticism (that dreaded, overhyped, overestimated thought process), discussion, and analysis of issues that other authorities have agreed to take seriously. Professors, especially in the humanities and social sciences, require students to rely on peer-reviewed authority because most of it is assertive by nature, not evidentiary. And whose assertions can we trust, after all? Professors know how hard it is to navigate among responsible and irresponsible assertions and opinions, to find the truth buried in the rhetoric. These databases try to put you (or your friendly librarian) in the driver's seat, presumably to save the enormous amount of time it takes to find your way on a sprawling roadmap of possible destinations.They try to establish and exemplify norms of evaluating information. Turn left here, and right there. But we are passenger-seated drivers on the information highway. Signs convince us we have arrived where we intended to go. Meanwhile, the hitchhikers get to explore all the little-known local attractions, eat the home-cooked meals and write the best guidebooks.By way of contrast, most science databases depend on the scientific inquiry process itself - "evidence-based, testable observation" - to act as the natural filter for distilling authority from information. Scientists are so certain of their authority they sometimes offer it for free - or for huge grant-eating fees paid by anonymous industrial donors. But though the observable, testable world is considered the "peer" that validates the observations, all observations aren't explained by science. One must still have a kind of faith to believe anything is true. For many, only the use of the entire Web can affirm that Faith. -PW

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

That ol' Search Engine, Time

"Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past"

- T.S. Eliot (Burnt Norton)

How much time does it take to think of something new - a poem, a scientific theory, a song, a conspiracy? Can we watch it happen? Is the time it takes to think of something preserved in the product? What is it about Time - the most unsolvable puzzle life offers - that makes us want to "save" it so much - librarians in particular? Countless songs, books, poems, symphonies, theories, myths and scientific studies have been devoted to preserving time, or lamenting its loss - and yet no one is willing to accept the obvious: that it can't be saved. This is a fact of death, more than a fact of life. Time is the cost of living; the more you invest in life, the more you spend of it. We all have only the time given us, but we always want more. This is one reason I remain perpetually skeptical about the need for - or value of - speeding up research and research tools.

Many information professionals believe that productivity is victimized by time, as if we'll miss learning something important if it takes too long. Yet nothing that we want to keep has ever been produced quickly. Information competes with pleasure, biology, habit, fear, family and purpose for our attention, and all must be given their due. It might be fun to dramatize time here a little, make it more visible, if not controllable. Our blogging software doesn't allow me to embed a stopwatch, but you can get to one easily enough. Firefox offers a good one as an extension, which you can download at Stopwatch . If you can't do that, you can find a java-based stopwatch application at Web-clock ; it counts in milliseconds. The Firefox stopwatch doesn't take up much room on a desktop, and a web-based stopwatch page can be minimized so that it can be used with other pages. If you resize your webpage you'll be able to keep the stopwatch visible next to it. You can also download stopwatches, both as free or fee-based software. These will give you much more flexibility in placing them and using them.

Do we know how long it took for Einstein to formulate his General Theory of Relativity in 1915, e=mc2? Those who knew him or have written biographies might say it took him 2 months, or perhaps two years, of really intense thinking. Some say it took eight years. Thinking isn't research, exactly, but we know Einstein was aware of his predecessors in theoretical physics - Mach, Maxwell, Lorentz, Poincare.....

There's another way of looking at it. Maybe it took Einstein only 3 billionths of a second to think of the Theory. How would we know? Where and when does a thought begin, or end? Has anyone figured out how to measure the speed of the thought process yet? Many think they have. Numbers can be so convincing, and there are more numbers than facts. Does consciousness even exist in time? Some neurobiologists insist it should be treated as a new branch of physics. We know the brain has trillions of neurons, which are powered by chemicals, atoms, forces, electrons..... Physicists agree that the fastest speed known is the "speed of light" - 186,000 miles per second (the cin Einstein's famous formula). How fast is that? Haven't you ever wondered how the speed of light could be squared? Squared, it's 34, 459,610,000 units. What is that a measurement of? It couldn't be a measurement of speed any faster than light, could it? It's a measurement of space or energy or mass. We already know that light establishes the ultimate measurable speed. Not very coincidentally, the speed of light is also the highest speed that the "movement" of electrons can be measured. Keep that fact on hold. Multiplied by matter, c2 is said to be measuring an equivalent of energy: e=mc2. In miles crepresents a "distance" of 186,000 seconds, or 51.67 hours, and c2 takes 1097 years. Of energy divided by mass? What is that? I don't know: I'm no Einstein. A light-year is said to be the distance light can travel in a year: 5,865,696,000,000 miles. But are hours, days or years energy? Can time energize? Does a mile exist outside time, or time outside of space?

They say all measurements are relative to the measurer. Then isn't knowledge proof that time travel is possible? In 3 billionths of a second light - and electricity - travels about 2.95 feet. But electrons can cross the width of a normal human brain, assuming the brain occupies only that spongy mass in your skull - about 7 inches - in far less than 3 billionths of a second - in one 600,000,000th of a second in fact. So what does that tell us? That Einstein was a fast thinker, that computers by definition could never think? If a brain - or a computer - has a billion circuits going at once in all directions, what does that say about the relative measurement of light, or thought? After all, our capacity to measure is still limited to the three dimensions we know. Maybe all those other "directions" are actually dimensions. To me, these musings suggest that thinking may be faster than light, or slower than is measurable in a single lifetime. Or both. What does it mean when Google shows it found 108 million references to "Einstein" in .017 seconds? Or finds 14,900 references to "einstein (and) e=mc2" in .26 seconds? No human can do that. But who asked Google to search, and why? Can we know when a search engine actually finds something of value? Or does thinking, that endlessly instantaneous process, have to intervene somewhere? Will search engines ever be able to speed up thinking?

There are hundreds of

time measurements, and ways of measuring time, from the Planck moment (10 to the minus-44 power of a second), currently considered the shortest describable duration - the one (the only one?) which may have lasted long enough for the universe to form - to the speed of light, used to measure the real estate of universes. But wait. There is also quantum time, which doesn't really involve measurement (too primitive a concept) or linearity. There is the Eternal Present (which you just missed). There is generational time, geological time, historical time, warped time, sidereal time, millennial time, vacation time, lunch time, subatomic time, dog-years, cellular time, billable hours, time off, watched pots, stopped time, doing time, bed time, keeping time, making time, having a good time, time wasted, dream time, too little time, forever (and ever), the time it takes to live, write, read and study Proust's Remembrance of Things Past...and that disfiguring, untreatable but legal addiction affecting a small minority of privileged misfits (including this writer) - extra time.

Putting a stopwatch on your desktop changes your perspective on time and online searching, especially when you see hundredths of a second whiz by. Milliseconds can't truly be seen by the eye, though the eye is what sees the results of Google searches rounded off to milliseconds. What can you do in a hundredth of a second? Some studies show it takes at least 5 hundredths to blink an eye. In one hundredth, light in a vacuum can travel 1860 miles, a crow's flight from Stony Brook to

All right. You have decided on how to search. You're going to go with the ever-reliable Academic Search Premier. Milliseconds continue to disappear while you manipulate your mouse or keyboard in a way that allows your browser to find the search screen when you touch something with your finger. Digital behavior. Or are you using a new voice-activated computer? You have a fast connection, and virus protection. Good. In only 2.12 seconds the website appears. If you're chatting a question, you'd better allow for time to pass on the other end, while your answering human becomes "live." By the time that happens, light could have made a trip to the moon and back hundreds of times. It could have been worse: the appearance e of the ASP database might have taken 3.4 seconds, or even - unthinkably - 6 seconds, if traffic was bad. Or maybe a better machine, better software, or a better connection would have made it faster - how about .074 seconds from click to screen! - even though the signals may traveled thousands of miles over 7 different relays. But a signal should be able to handle such small distances - however old your region's electrical grid is. After all, signals can travel 186,000 miles in a second. In a vacuum.

The basic

Academic Search Premier screen (members only!) - once you find it - is pretty easy to negotiate. As with most search screens, you have relatively few options to consider - only 3, or maybe 6. Maybe 11? Only the stopwatch knows. Your chief decision will be, what terms to search. That's easy. We can use "impact" (or is that the right word? What about "influence" or "effect" or "outcome"?) and "einstein" (does capital E matter?) and "War?" (which war? Two? 2? II?

Never mind. It turns out that "einstein and war" (with no limits set) does produce at least 97 references. Should we go down the list and see which ones may interest us? How about New Details Emerge from the Einstein Files, by: Overbye, Dennis. New York Times, 5/7/2002, Vol. 151 Issue 52111, pD1, 0p, 1 chart, 16bw; (AN 6614828), reference number 38 on page four of the screen. I guess you had to be there. Well.... if we add "atomic" to the search, it narrows it down to only eleven. That may work better. "Relativity" instead of atomic" yields 6. Hmmmmmm. What if instead we want to see how this search displays in a colorful graphics mode, not a list? (Forget the stopwatch.) What a brilliant idea! Who thought of that? If you happen to look at the top of the basic Academic Search Premier search page, you'll see "Visual Search" on the middle tab. Click it, go ahead! Thanks to Grokker, a dynamic, hypermediated screen appears that puts information in a whole new light:

This certainly looks like more fun. The info is inside a "globe"! Plus: the globe already separates subtopics for you (based on what kind of tagging? Don't ask: somebody had to do it!) Click on one of the small circles, like "World War," or one of the small squares within them, and further refinements appear, until, at last, you are given specific references to articles like the ones we started with, though in a different order. Will the order we find them in really make a difference to our research? Maybe. Who Knows? The fact is, we will never know. Even if a study showed that it did, would a brilliant researcher tailor his search tactics to findings based on studying an experimental model (using inevitably outdated references)? He might if an articulate librarian showed him it was "advantageous," though the librarian researcher will need time (using who's time?) to explore all the ways she can refine a search using this one engine (not even Google does the Grok for you). But with that stopwatch going, how could anyone spare that much time?

Most librarians and search engine developers take pride in the time they claim they can save people who are looking for information - whether it's the best price for a pair of Guess jeans, a new Thai restaurant on the North End, 5 articles on teenage gangs in Singapore, or the latest treatment for pancreatic cancer. We - and our users - continue to promote speedy searching - by teaching users how to search and research, by using different engines and strategies, by designing new search engines. Our users expect us to, and get darned impatient if we take too long. And we do save time. The problem with this outcome is that the only time we save is human time, and neither searching nor faith nor scientific knowledge is measurable in human time. Internet search engines can improve searches for specific information, information that is embedded, in a sense, in descriptive tags (even a title is a tag), though nearly every search engine will link to "related search terms". Librarians re-shape "why" questions from users (even Jeeves got tired of being Asked "why?") because such questions can go in so many directions. It may take lots of time to find the end of "why." "Why does time sometimes go slowly and sometimes quickly?" "Why are artists so crazy?" "Why is the sky blue?" Ignorance can't be squashed by generalization. Its coin is time and education costs a lot of coins.

Then perhaps we should use a different kind of stopwatch. One that measures time lapses in fractions of a year would show that a successful 20-minute search, using several strategies, back-tracking, and sampling, takes only 38 ten-thousandths of a year to accomplish. How incredibly fast is that? How quickly we learn! Would you really need to cut down your search time to a speedier 11 ten-thousandths of a year by eliminating one of the steps in the thought process? What would you do with those extra 27 ten-thousandths of a year? On your millisecond stopwatch, it'll go by before you can think of a good answer. There's never enough time to learn: a puzzlement, a paradox, a false dichotomy? Or am I just spinning an issue out of too much time?

Consider the time it takes to learn, to think. Has anyone really studied the connection between research and thinking? That they are connected is usually an a priori assumption. Many people have measured the time it takes to learn, but all they have come up with are numbers telling us who (or what animal) learned what was already known, or knowable, and under what circumstances. Which is fine: all most of us need to learn are the facts of life and the right way to the dead end of the maze. Education and research, however,deal with how people think. There are ways to re-define thinking, but the measurement of it is always surprisingly different from the size of the thought. Intellectual history traces the origins and development of ideas, and often assigns dates to them, but it measures outcome, not process. Are the origins of ideas separate from the process of thinking? When it comes to thinking, all time is equal - or irrelevant. Why spend time trying to save seconds, minutes, hours or even days from the search for knowledge when we don't even know how long thinking takes to become knowledge? A bad habit, I suppose, akin to human error. Forgivable when inconsequential or productive. After all, saving time can be profitable, even fun! Sesame Street proved it, and so does NASCAR. And look how much time we spend in thinking why we didn't get the terrorists in time to prevent their acts of violence! The Report of the 9-11 Commission made findings out of unanswerable questions that had to be asked about the day that time stopped, then, infuriatingly, just kept on coming. And a good algorithm will turn these findings inside out.

Paul B. Wiener

Sept. 11, 2006

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Freaks from Brooklyn

Let’s go on a little fishing trip. There’s nothing else I can call it: you’re at a website you wanted to be at, you start exploring it, and then….maybe that site’s URL is intriguing. Or maybe you see all those tempting topical links that the page’s author felt just had to be there. One of them looks sort of promising. You click on it, and …..oops! You’re hooked! Suddenly you’re on a very different page. Who’s doing the fishing?

A couple of weeks ago I went to an art exhibit in an old converted warehouse on the water in Red Hook, Brooklyn. I saw many works I liked, but one in particular struck me, and I thought I’d check the artist out later. I liked his ultra-realistic display of a creepy, deadly animal, mocked up as a commercial marketing label. Why did this attract me? I can think of reasons, as I’m sure you can. But there are no reasons. It just did. It was easy enough to remember the artist’s name: Takeshi Yamada. But what about him?

Later that night I Googled him, and quickly found him, among other places, at http://sideshowworld.com/SSA-15.html. A biography there told me the usual things that made someone artistic and unique, nothing very personal or exact, like his age or what his life in Japan was like before he moved to the USA at the age of 23. He described himself as a creator of Superrealist art, among other things - one of my favorite genres, and right there was a large array of thumbnail photos of his work, including the very one that had caught my attention!

The URL for this website – the part before the backslash - suggested that there might be more where this came from. Don’t you ever play around with URLs, especially long ones that attach jpegs or pdfs, wmvs or lengthy proprietary extensions? You wonder what came before the backslash, especially when there are 3 or 4 compound addresses in the URL. The address before this backslash was http://sideshowworld.com/, and it turned out to be a gigantic website containing hundreds of links about every aspect of sideshows you never knew existed, as well as dozens of on- and offline exhibitions, many of which were sideshows in their own right.

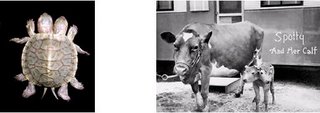

It didn’t take me long to select a link from the dozens. I chose The Barnyard Freak Show – don’t ask me why – where I came upon images like these:

But the appeal of historic freakish animals only went so far. There was also a link to the Live Deformed Frog Cam that a Minnesota State Agency had had the foresight to mount. It sounded promising, but it took too long for the frog to show any signs of life. You try living in front of a webcam! Anyway, anyone can be deformed. Another link to Fairly Freaky Animals yielded a purple bear, albeit one whose color had limited tenure. Below these were thumbnail links to images of posters advertising these shows, such as the tempting “Ducks with Four Wings,” very sociable birds, evidently, that won’t be found in any Peterson’s Guide, or works of imagination depicting freaks still unborn.

The “links” link from any website is always a tantalizing fishing hole, and the catch is never predictable. Sideshow’s is no exception, and it leads away from the pages Sideshow maintains. For example, from “General Sideshow Links” you will find The Human Marvels, a blog published by a Gothic-looking gentleman named J. Tithonus Pednaud that’s dedicated to unique individuals like the ones below:

It looked like Tithonus, who has a large presence on MySpace, needed to be reassured about something, and I e-mailed him, telling him I too was a freak, though it wasn’t very obvious from my appearance. But he never answered back. On the inevitable blogroll list of The Human Marvels were links to similar blogs, including boingboing, a popular site that calls itself “a directory of wonderful things,” implying that things needn’t be freakish or odd to be weirdly fascinating. Another link from Sideshow’s “links” page went to House of Deception, a similar site that features links to other carnivalesque phenomena, like the “deceptive” world of wrestling. Did you know there was a sports subculture devoted to midget wrestlers like Cowboy Bradley and Little Darling Dagmar? What is the point of this information? I haven’t a clue.

But let’s take linking a step further, into the world of social software. Let’s say you’re already a member of the well-known del.icio.us community – a wiki-type place that allows members to post and store their favorite links, as well as tag them, share them, search them, cross-link them, and retrieve them from anywhere. Finding users with compatible informational interests and tagging tendencies is easy and can lead to serendipitous or ingenious ways of finding new sources – of arcana, if nothing else. Let’s say del.icio.us user “Manofletters” decides to add House of Deception to the del.icio.us bookmark database, and he tags it with “odd”, “freaks”, and “performance.” Any words can be used to tag it, and other members can add their own tags.

Once House of Deception is entered into the del.icio.us database, the number of times anyone else has entered or copied it will be displayed. Sometimes no one has, and sometimes no one ever will copy your bookmark. But usually, someone has or will. Their tags and mine will be displayed. True, “odd” is pretty vague - maybe I should have chosen “weird” - but it’ll have to do for now. The screen names of everyone who has copied House of Deception will also be displayed. If you click on a screenname, his or her other bookmarks and favorite tags will be displayed. And on and on… All these things will be hyperlinked, networked and searchable. You users of MySpace, Flickr, YouTube or LastFM will be familiar with the pleasures of networking your preferences. It’s addictive. If you search the “odd” tag on del.icio.us (del.icio.us/tag/odd) you will find such oddities as The Blue Ball Machine, Strange Statues around the World, and Strange Attractor, a terrific British zine “celebrating unpopular culture” - but few, if any, links to “freaks.” If you search del.icio.us/tag/freaks you’ll have better luck, but don’t blame me for what you might find.

Friday, June 30, 2006

A Thousand Words or So

by Paul B. Wiener

One way is by visiting web sites with names that provide no clues about their content. And when the site appears, what’s visible also isn’t much of a clue. Not right away.

One such site is Dredge, produced by a group of electronic media students in our own Department of Art. (And fittingly, you won’t find it listed anywhere by using the anemic search engine on Stony Brook’s Home Page either, though I’m sure that wasn’t the students’ intention.) Virtually nothing on Dredge’s front page tells you what it is – a display site for artistic productions and experiments. Instead, you have to look for the hyperlinks across a large dark, teasing space until you decide that those things down there must be the links. The search process is prompted by the page design. Your “visual brain” is forced to overrule your “textual brain.” Many clueless sites are like Dredge, visually stunning, often textless pages made by people in the arts - photographers, cartoonists, graphics freaks, website designers, Adobe acrobats, hashers, neo-cartographers, poets, topologists - even scientists and farsighted young entrepreneurs like Alex Tew, who invented the Million Dollar Home Page. These people love the challenge of picturing those famous thousand words before you can even think of them. Think of the information gained as similar to what we learn from our dreams, even though they don’t have subtitles.

Another quirky graphic artist’s page that lets you decide how to find its informational content is Leif Parsons’ Page. And another is Ian Timourian’s Mandalabrot.net, which focuses on fractals, visual remixes, generative design, and many of the other new forms of art made possible by computer technology. The site Visual Complexity studies the visual display of information by, well, showing it off. It stuns you with its opening page that presents hundreds of unexplained proprietary information design templates. Bit offers some verbal encouragement too: “Functional visualizations are more than innovative statistical analyses and computational algorithms. They must make sense to the user and require a visual language system that uses colour, shape, line, hierarchy and composition to communicate clearly and appropriately, much like the alphabetic and character-based languages used worldwide between humans.”

Even political forums on the web can score points without using words, animating information to appeal to the newer kinds of “information literacy”. Many web sites and blogs, like GPrime.net, Molecular Expressions, and An Atlas of Cyberspaces, use text to introduce links to the latest text-free games, special effects photography, cartography, optical illusions, digital video and flash animations. And let’s not forget the latest craze, the ever-teasing YouTube. These sites offer learning experiences that can be visually instructive far more quickly than they can be explained – or justified - in words.

Information as most librarians and scholars know it uses symbols – not only words, but numbers, formulae, marks – as well as color and sound, to communicate and document experience. More importantly, most librarians use language to describe the symbols. Symbols called “words” tag ideas, facts, events, people, experiences, memories, feelings, observations. We use them to organize various attributes and similarities. The world thus described is sometimes called “recorded history,” sometimes “science,” and sometimes “reality,” and sometimes “searchable.” What do we do about the information that cannot be so described - the recorded stuff that can only be perceived non-verbally? Do we translate it into words? How many translations (copies, messengers, media, generations, reproductions) will records survive before they lose “authenticity”, whatever that is? This problem long intrigued the philosopher Walter Benjamin, who applied it to works of art. But he wrote it before the internet existed. One answer seems to be: some records survive translation better than other records, and better than most works of art.

There’s a fascinating website that draws attention to the paradoxical fact that art reproduced on the web, because it is “lighted from within,” is sometimes more beautiful than the original thing. Before you leave, take a look at Bibliodyssey, a blog about the beauty of book illustration, old and new. Strange concept - book illustration - isn’t it? Who needs it, especially today, when screens illuminate words everywhere? Illustrating books seemed normal enough once, but here you realize that you are celebrating “books” by reading a blog, (there were no “blogs” three years ago), on a computer screen no doubt using a Windows-based GUI (coded in letters, numbers and signals), and looking at a digital image – one which presumably can never degrade, (since a digital fact weighs no more than an idea and can be dog-eared indefinitely) unless electrons themselves disappear into time….Here’s a lovely image of a drawing (click!) that someone scanned from a 500-year-old manuscript, whose maker once had it painted there by an artist – at this moment the “real one” probably sits unknown and untouchable on a shelf in an ancient library in Rouen, a library morphing into a museum. If most information isn’t art, is it still subject to the kind of degradation that copying and translating from any medium produces? And if the image (or the book, or the movie: remember Fahrenheit 451?) remains in my memory long after the printed and digitized one disappears, will it still be authentic?